Reading an Audiogram

How to Read and Understand Your Audiogram

Many health-related measurements are familiar to people, like perfect vision being represented as 20/20. However, how is healthy hearing quantified? Presented with the results of a hearing test, most people have no idea how to interpret what the graph—called an audiogram—reveals.

An audiogram may initially look like indecipherable lines and symbols on a graph, but learning how to interpret it gives you a much better understanding of your hearing. Your audiologist uses it to determine recommendations for addressing your hearing loss, so knowing how to read your audiogram means even better communication between you and your audiologist in mapping a treatment plan for you.

The goal of a diagnostic hearing evaluation

The goal of audiometric testing is to measure a person’s hearing ability across a range of frequencies, or pitches. Each ear is measured independently since hearing ability is not always the same in both ears. During a hearing evaluation, the audiologist will use headphones or earphones through which you listen for sounds, including beeps at various frequencies and recorded words. As you respond by depressing a handheld button when you hear beeps or by repeating back understood words, your hearing thresholds are plotted. A hearing threshold is the softest sound you can detect about 50% of the time.

Understanding frequency and loudness

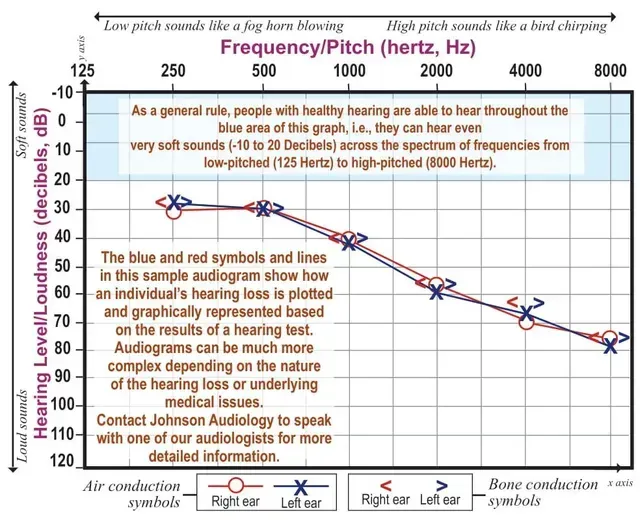

Look at the sample audiogram below. The horizontal axis (x) represents frequency, or pitch, from lowest to highest and is measured in hertz (Hz). Typically, the lowest frequency tested during a hearing diagnostic is 250 Hz; the highest is 8000 Hz. When you look at the x-axis that measures frequency, moving from left to right shows the frequency going from deep-sounding pitch to high pitched, much like the keys on a piano. Most human speech ranges from 250 to 6000 Hz. Vowel sounds (A, E, I, O, and U) are among the lowest frequencies and are responsible for loudness of speech. Consonants like S, F, SH, CH, H, TH, T and K sounds are among the highest frequencies and create clarity of speech. This is why hearing loss affects a person’s ability to understand words and conversations. If, for instance, a person has hearing loss that affects high frequency sounds, a word like “feet” begins to sound like “ee” as the letters F and T become indiscernible. Oftentimes, hearing loss occurs in the high frequencies first, which is why people often comment on hearing but not understanding. So, if you have been blaming your family of mumbling, it actually may be hearing loss.

The vertical axis (y) represents the intensity, or loudness, of sound and is measured in decibels (dB). A rifle being fired is a loud noise or a very high decibel sound. Rustling leaves are soft sounds or very low decibel.. Although the top left of the chart is labeled -10 dB or 0 dB, that does not indicate the absence of sound. A zero decibel reading actually represents the softest level of sound that the average person with normal hearing will hear, for any given frequency.

Understanding symbols on the graph

Several different symbols are used to indicate hearing thresholds on an audiogram, which create a quantitative “picture” of your hearing ability or loss. Testing with earphones or headphones is called air conduction testing because the sound must travel through the air of the ear canal to reach the inner ear. The organs of the inner ear then transmit the sound to the auditory nerve and on to the brain where sound is interpreted and assigned meaning. A red “O” denotes air conduction results for the right ear on an audiogram. The results for the left ear are marked with a blue “X." Bone conduction testing is completed by placing a device behind the ear on the mastoid bone. Sound is transmitted through the vibration of the mastoid bone, and results are marked on the audiogram with a “greater than (>) symbol” for the left ear and a “lesser than (<)” symbol for the right ear. Refer to the audiogram below for a visual reference of an audiogram.

Air and bone conduction and speech testing allow an audiologist to more precisely interpret and diagnose hearing loss. Each symbol (X or O, < or >) on the chart represents your threshold for a given frequency and, when plotted, represents overall hearing ability. In the sample audiogram, the individual's thresholds from 250 Hz through 8000 Hz denote hearing below normal in both ears. A person with this degree of hearing loss will struggle when there is background noise, with softer speech and when there are no visual cues and may complain that people mumble. This person would benefit greatly from hearing aids.

If audiogram symbols are essentially overlapping, hearing loss is considered symmetrical, or the same in both ears, like the sample audiogram shows. If the symbols do not overlap, your hearing loss is asymmetrical, meaning your ears have differing degrees of hearing loss. Your hearing loss also may show a pattern of loss that is generally flat or that is sloping or rising where some pitches are worse than others. Connecting the air conduction symbols makes the pattern obvious.

What is considered healthy hearing on an audiogram?

Take a look at the audiogram again. As a general rule, healthy hearing is represented in the blue shaded area above the 20 dB line that crosses the graph from left to right.* Any symbols below that shaded area, however, indicate hearing loss at those frequencies. Noteworthy is that hearing can be damaged by things like ear infections; medications; common household items like lawnmowers; noisy work environments; or a family history of hearing loss. (Find a list of common items that can cause hearing damage at johnsonaudiology.com/audiogram.)

Ultimately, when diagnosing and treating, your audiologist considers your audiogram, which represents quantitative measures, along with your perception of your overall listening challenges. Input from family members about communication difficulties also can be beneficial. Today’s sophisticated hearing aid technology is programmed to increase the sounds within the specific frequencies of your hearing loss. Thus, hearing aids are a great solution for restoring the sounds a person is missing, and early identification and treatment are keys to success.

A snapshot in time

Your audiogram is a snapshot in time of your hearing. It is a prescription for treating your hearing loss and a baseline for you and your audiologist. To monitor any changes in your hearing over time, routine testing is necessary. Knowing how to interpret your audiogram is a valuable skill, empowering you to make informed decisions. The information in this article is a basic interpretation of an audiogram. Audiograms can be more complex depending on the nature of the hearing loss or underlying medical issues.

*Some exceptions exist, such as when the person has very mild hearing loss but has tinnitus, or ringing in their ears.

Recent Posts